Art for all, inclusive art

Time and again, galleries, museums and special exhibitions are dedicated to the art of people with special abilities - even if they are commonly considered "disabled". At the Cultural site Wintringer Chapel, this impressive place of art and culture in the Saarbrücken region and the UNESCO Bliesgau Biosphere Reserve, there was another such inclusive art project at the end of 2023. Facilities for people with disabilities, schools and special studios promote artistic activity, especially the artistic creation of these people. Some of them seem to be gifted with very special skills, their handling of color, form and content is remarkable - regardless of their other abilities.

The simplicity of the room, the peace that emanates from it, made me think of "quiet rooms", which we would always like to have for people with special disabilities. Rooms that are not distracting, rooms where you can withdraw, rooms where you can quietly occupy yourself with something - perhaps an art object. An empty room, an object, a person.

Prof. Dr. Andreas Fröhlich

However, not all people are equally capable of artistic expression. Many more people go to museums, exhibitions, galleries and even churches to look at art than "make" art themselves. They want to enjoy old or new art, be inspired, find out what's new. They want to look, be surprised, perhaps even provoked. You want to participate in art

Participation in the cultural heritage of mankind ... is my personal definition of education. Being able to participate in what people have thought, written, composed, analyzed, constructed or formulated. This also includes everything we call art: Music, poetry, dance, theater, opera, painting, building and sculpture. At the beginning of his incarnation, early man carved small figurines from bones, created symbols, painted pictures on walls and thus created art. Art is obviously part of the oldest cultural heritage of mankind.

Restrictions

What is the situation regarding access to art and art objects for people with sensory impairments? Even for blind or visually impaired people it is difficult, sometimes there are special guided tours in museums where they are allowed to touch objects. Hands in white cotton gloves so that the art objects do not come into contact with skin. But even the skin does not come into contact with the objects, it is an indirect feeling and touch, as if sighted people had to look through a slightly milky pane.

Pictures and colors are explained linguistically for those who cannot see, but what is the spoken YELLOW for someone who has never seen yellow? Sometimes specially embossed foils are also offered on which you can feel contours that are supposed to correspond to what can be seen in a picture.

It is hard to imagine what impression art can still make.

For people with more severe, multiple impairments, there are almost no access options; participation in this heritage, even in the simplest form, is denied them: they are not allowed to touch an object, hold it in their arms, get very close to it to sniff or feel it. You are only allowed to look at it. In our culture, art is something to look at, something you have to keep a certain distance from. But very many of you can hardly orient yourselves visually, i.e. your sight offers you no useful information. What's more, some of you don't understand language either, so we don't know how you perceive your environment and the people in it. How could they understand art?

Understanding art

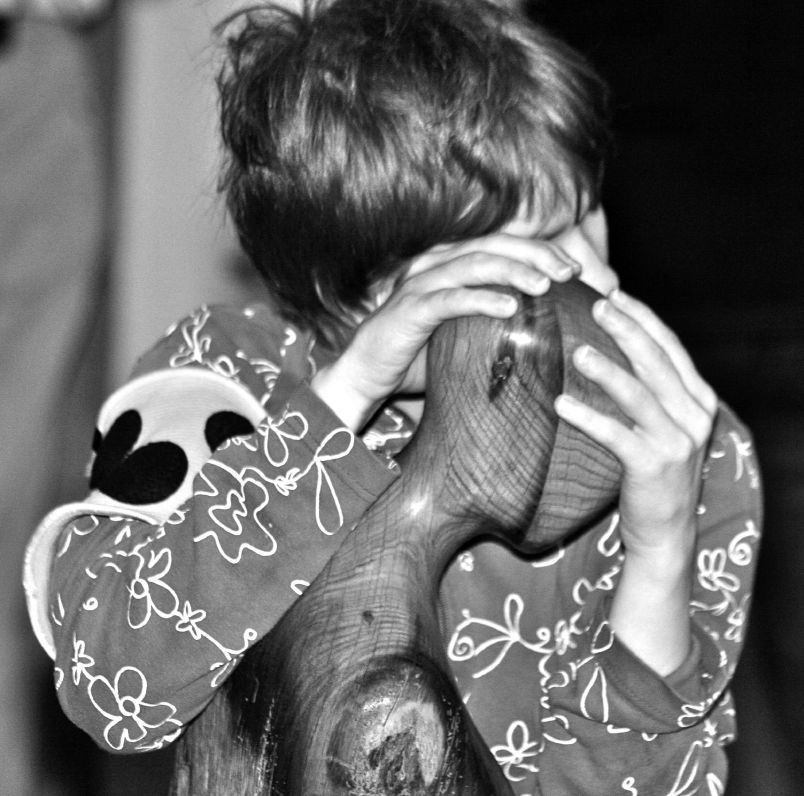

A double meaning that is self-explanatory: the initial activity is the touch, the direct, searching contact between the person and the art object. Subject and object meet, the object offers "resistance", is hard, perhaps cold and initially alien. The touch, the moving hand on the surface, the contact between an animate and an inanimate body slowly give rise to a form. Depth, circumference, form, surface and material become a unity that we describe as a shape.

This is exactly how we began to understand the world as newborns. We came into contact with an object, felt it and began to "explore" it.

First of all, probably with the mouth: the mother's breast, soon our own fingers, a pacifier, later the rattle, the nose of a teddy bear. We learned to distinguish between animate and inanimate, between that which moves and that which remains motionless. Living beings and things. We tried to make these things move: nudging them, hitting them, dropping them - but we soon realized that this didn't make them come alive.

We learned all of this through sensory or motor skills, far from using the concepts that language conveys to us. We felt, held, let go, grasped, kept using our mouths, collected surfaces, structures, temperatures, materials and shapes.

With these experiences, this sensed knowledge of things, we can now, as adults, learn a great deal about the things around us through sight alone. We have already learned a lot, we can distinguish surfaces with our eyes without touching them. A wooden figure is something completely different to us than one made of bronze - just by looking at it. We see the different surfaces, we even see the different weight, the material. We no longer need to touch the object. Sometimes, however, we would like to secretly touch it ourselves to make sure, to get a more concrete impression. It is precisely this concrete impression that I would like to give impaired people.

Realizations

I have spent my entire professional life helping people like this, people who need direct physical contact with other people in order to perceive them at all, who also need this contact with objects in order to understand something. Actually grasping, in the original sense of the word: touching, feeling, holding, embracing.

I am particularly interested in the question of how to enable children to participate in art. How do you create the opportunity for them to encounter art? How should this art be structured so that it can also be experienced by people who use perceptions other than just looking at something with their eyes?

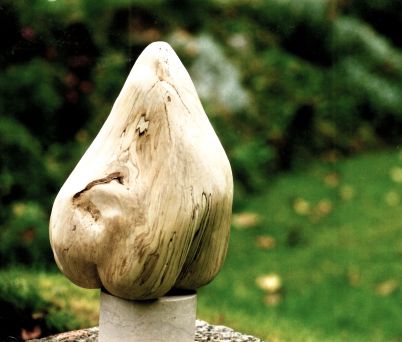

Years ago, I made a sculpture, a bud, for children in an Italian institution for blind and visually impaired children with multiple disabilities. The birch wood sculpture was intended to give them the opportunity to feel: now I am right here again, in this house. Just like when we recognize a certain statue, a certain picture in an entrance hall and know that it belongs to this building, I have arrived.

A second wooden art object comes from a maple tree that once stood in our garden and of which I had kept a piece for many years. I had started to work on it, but then left it again because I wasn't making any progress. Now, with this idea of an immediate "basic" art object, the block of wood also told me what it wanted to become.

The surface is completely designed to be touched. I have worked out different, fine structures and left natural growths. The wood remains completely untreated - if someone were to lick it, it wouldn't be a shame. There are corners and edges, but they are gently rounded. You can't hurt yourself.

You don't have to recognize anything specific in this object, you don't have to know anything, you don't have to understand anything. Simply come into contact (= touch), feel it. The object is thus entirely in the tradition of concrete art, it is not a copy, not a representation of something, it has no secret meaning, it is not a symbol. It is what it is.

A heavy block of maple for some to look at, for others to touch, feel and smell. You can take it off its base, the brass rod is only inserted into the wood. Then you can grasp the whole thing, feel its heaviness, its temperature, its strength. And perhaps you can search for further impressions in the holes and small cavities.

The wood will certainly change when many children's and adults' hands actually stroke it. That's part of it - they are supposed to be art encounters, and they always have a reciprocal effect. This is of course a challenge, especially for all museum curators, but also for the artists themselves: when it has taken shape through the hands of its creator, when it is "finished", then no one is allowed to touch it. What until this moment was a creative act, working with the hands, is now a destructive act. "Please do not touch".

The object is removed from any direct contact - and this is precisely what needs to be broken if art is to be made accessible to certain people who have to live with severe limitations.

I wanted to go down this path with my work, even though I'm certainly not an "artist", more of a dilettante who can do things that are hardly possible, at least for commercial art.

I followed my scientific insights from decades before and tried to make something of them.

The result is a stele made of soft, light-colored poplar wood. You can roll very close to it in a wheelchair, for example, feel the undulating surface, perhaps even look through the opening and recognize a familiar face on the other side. You can hold the stele with both arms.

In a Swiss facility for deaf-blind people, there is another maple block, angular, at first glance "rugged", but when you touch it, soft: slightly rounded surfaces, breaks and edges that lead to new surfaces. Perhaps a kind of "hike" through the mountain world? This block can also be removed from its base, placed on the ground and then explored from a safe position.

The staff at a center in Marseille wanted an object to hang in the large stairwell.

A piece of a plum tree was turned into a flowing, smooth sculpture that is very comfortable to lay on your lap, its flattering surface inviting you to feel further and further beforehand.

And there, in this facility, there is a great janitor who thought about how children and young people with severe motor and mental impairments could get really close to this suspended object. He invented a table that can be driven under with a wheelchair so that you can get really close to the object. And you can even lower it on the rope, it then lies on the table, can be held in your arms, can be explored with your mouth...

Outlook

These objects are not about therapy or perception training. It is about an open encounter with designed material, about the very individual discovery of the attractive, beautiful or even the surprising and strange.

I would like to see at least one art object in every art museum that can be viewed, touched and experienced directly by the senses: for children, for old people who can no longer see well, for people with visual impairments and also for people with severe and multiple disabilities.

Kunstpalast Düsseldorf has opened an exhibition of large sculptures by the British-German artist Tony Cragg at the beginning of 2024. At the artist's express wish, the exhibition is called Please Touch. And this is not only allowed in this exhibition, it is encouraged. Encountering art enriches you and allows you to participate in the cultural heritage of mankind.

Such "basic" art objects by him can currently be found in the following institutions:

General special school in Zams, Austria

Andreas-Fröhlich-School in Krautheim, Germany

School of the residential home for children with severe multiple disabilities in Karlsruhe, Germany

Tanne Center for deafblind people in Langnau am Albis, Switzerland

Etablissement pour Enfants et Adolescentes Polyhandicapés Decanis in Marseille, France

Further art objects are currently in the works.

Andreas Fröhlich worked for many years as an educator at the Rehabilitation Center Westpfalz in Landstuhl. After completing his doctorate, he took on a deputy professorship at the Rhineland-Palatinate University of Education in Mainz, followed by a professorship at the Heidelberg University of Education and then worked at the former University of Koblenz-Landau in Landau until his retirement.

Download